We knew this was coming. This month, Governor Newsom announced the extension of a drought emergency declaration to 50 of California’s 58 counties and asked residents statewide to reduce water usage by at least 15%. That means that every Bay Area county except one (San Francisco) is now under the state’s drought emergency declaration. Local water agencies have gone even further by seeking greater reductions and imposing limitations on outdoor water use.

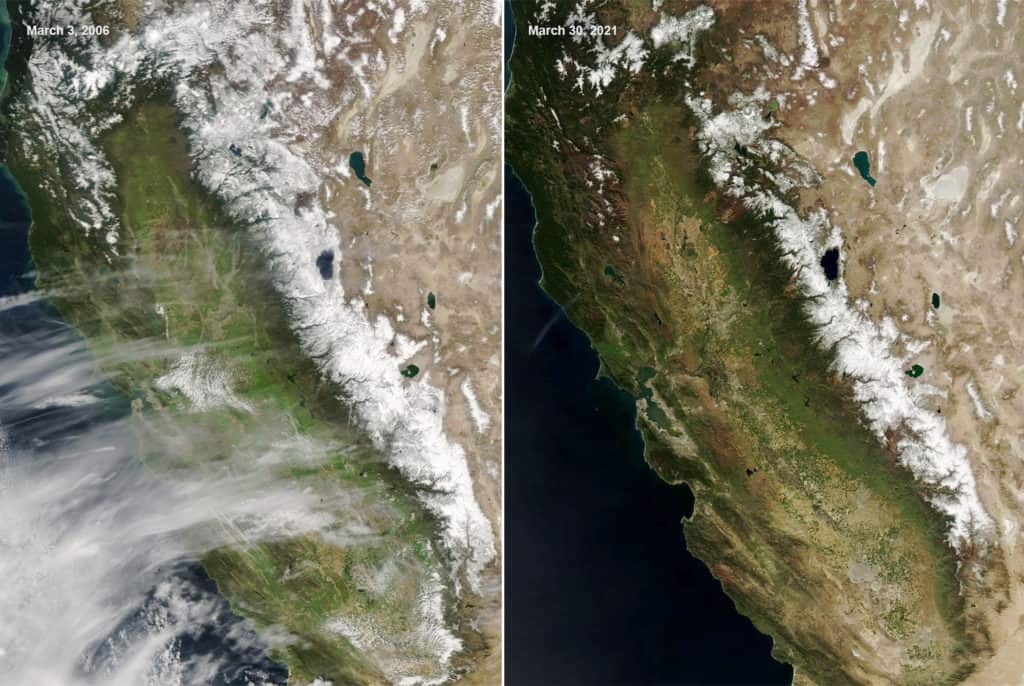

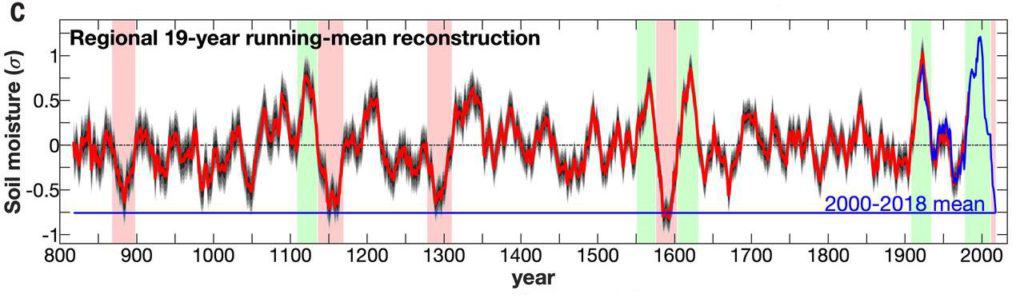

Drought is not unfamiliar to Californians. Our state’s climate has historically been characterized by extended dry periods broken up by rainy years. But it is now clear that human-caused climate change is making California hotter and drier, and that droughts are becoming more severe as a result. The current “mega drought” appears to be the driest period that the American West has experienced in at least 1,200 years. Mega droughts are not only drier than average droughts, but also last decades rather than years.

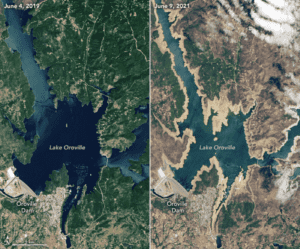

Even when rain and snow are plentiful, much of the state relies on an engineered system of dams and canals to move water from the north and the Sierra Nevada to provide drinking water and irrigation in the Bay Area, Southern California, and the Central Valley. Climate change is challenging that system as reservoirs reach historic lows and the Sierra snowpack is now predicted to provide nearly 80% less water by 2100. Hot, dry conditions and water scarcity will be our reality moving forward. We need to plan for what the Bay Area of the future looks like, and how to ensure that we use water wisely.

Impacts

California’s freshwater system balances a set of competing demands from residential users, agriculture, industry, and ecological concerns. Extended drought threatens to pit those interests against each other in ways that can be incredibly damaging. Competition for limited water has already led to concerns that salmon populations, which travel through the SF Bay on their way to spawn along the Sacramento River, are threatened with extinction.

As the resource becomes scarce, local water providers end up purchasing excess water from other parts of the state (EBMUD & Valley Water have announced such purchases), which can lead to rate increases that are particularly challenging for communities who already struggle to afford basic utilities. In fact, water debt has expanded during the pandemic, and studies confirm that racial inequalities create higher concentrations of debt in Black and Latino communities.

The budget deal approved by the legislature and the governor includes approximately $3 billion to address the drought, including new water infrastructure projects, wildlife protections, and community assistance. It also includes $1 billion for water debt relief, to help ensure that people who struggled to afford their water bill during the pandemic are not threatened with water shutoffs during this hot, dry summer.

Looking Ahead

Urban areas use a relatively low amount of the state’s overall water demand, but here in the Bay Area we have already been taking steps to ensure that our communities embrace the reality of this extended and extreme drought. Water districts offer rebates and incentives to repair leaks, reduce use, and convert landscaping to drought-tolerant alternatives. But bigger changes are also needed.

Inspired by the last drought, in 2015 San Francisco became the first city in the nation to require new development include on-site water reuse systems for non-potable uses. That means that rainwater and greywater (think sinks and washing machines) are used for on-site irrigation and toilet flushing instead of drawing on San Francisco’s supply of pristine drinking water from Hetch Hetchy.

Valley Water in San Jose created the Silicon Valley Advanced Water Purification Center to filter wastewater for reuse. The State Water Board has created policies to ensure recycled water meets stringent standards. Currently, the water produced by this system is used for irrigation, but in the future it could provide a new source of drinking water for South Bay residents.

How we grow as a region will also play a role. Urban sprawl is known to increase air pollution as commuters clog highways. Expansive low-density communities are also less water-efficient, using nearly twice as much water (mainly for landscaping) as urban neighborhoods. Changing our development patterns toward denser, transit-oriented growth will not only reduce greenhouse gas emissions but will also promote water conservation.

These changes require significant investment, and the State needs to help cities improve their resilience to drought by providing new funding support. This year’s state budget certainly makes big steps in that direction, but as the drought is going to persist so will the funding need. Climate resilience should remain a priority for the legislature going forward.

In 1915, during another period of drought, local leaders around the state took to paying a man named Hatfield, a self-proclaimed “moisture accelerator”, to produce rain on demand. He was eventually discovered to be the charlatan that he was, but not before receiving large amounts of public money for his efforts. Today’s leaders need to be guided by science, not superstition, and invest in real solutions that provide resilience. Empty promises and false hope are not going to solve our climate challenges. Only a coordinated effort to improve our infrastructure and provide for our communities will ensure that California is able to weather the storm, or rather the lack of one.