How many trash bags worth of waste are flowing into the San Francisco Bay starting this year? Supposedly, zero. The truth is a bit more complicated. The Clean Water Act requires the elimination of stormwater trash pollution from San Francisco Bay, which cities have spent the past 15 years working to make real. Given the over a decade-long time frame, why have some cities still not met this goal? And what can be done to reach it?

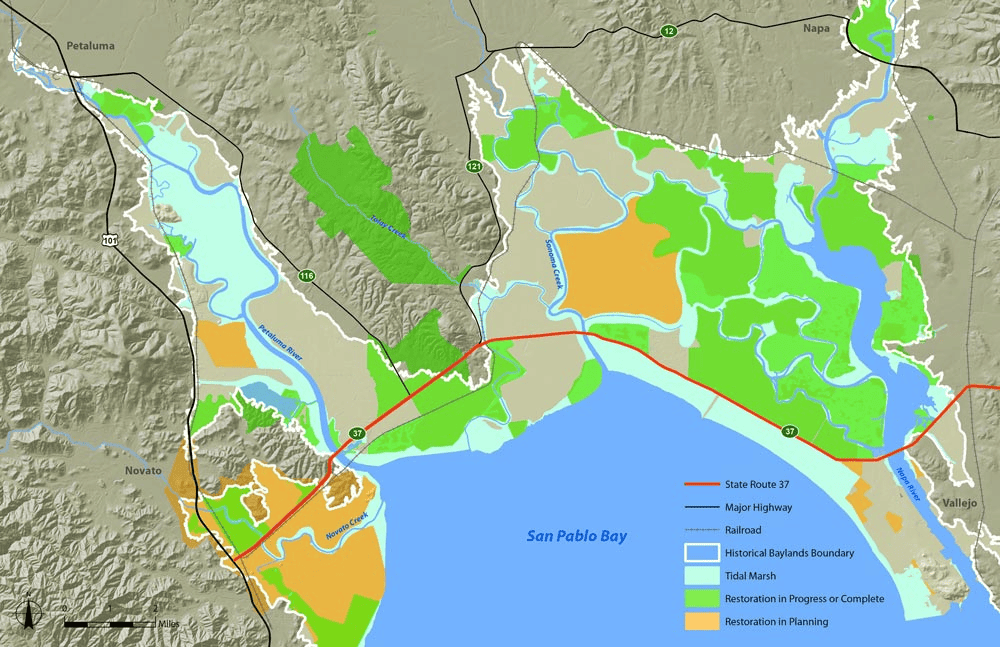

California has been a regulatory leader in clean water for decades, with our actions even inspiring parts of the national 1972 Clean Water Act. Using this landmark law authority, in 2009 more than 70 cities in the Bay Area were given stormwater trash discharge requirements that became stricter over time with the goal of preventing all trash pollution from stormwater systems by 2025. This June, the deadline for these cities to keep stormwater trash out of the Bay came and went. Most cities made this deadline, and of the 21 cities who did not, 11 cities forecast that they will reach compliance by the end of 2025.

Why is trash a pollutant that cities are required to keep from entering the San Francisco Bay?

During the rainy season, which we have now officially entered, stormwater floods our city streets. In a natural landscape, stormwater can permeate the soil and get taken up by plants. However, with increasing development and urbanization, most of our cities are covered in impermeable surfaces like pavement leaving stormwater nowhere to drain. Instead of letting it pool and flood city streets, we have storm drain systems.

Storm drains give rainfall an escape route into creeks or the Bay. Historically, water that flows through storm drains is not treated in any way. Unfortunately, this system also creates the opportunity for trash flow superhighways, where mostly plastic litter (objects like cigarette butts or food wrappers) gets flushed into the Bay and its waterways. Trash then builds up on our shorelines, harms wildlife, and contributes to the growth of microplastics in our water. Even larger plastic objects can break down into microscopic pieces of plastic that stay in ecosystems for hundreds of years and have numerous negative environmental and human health impacts. The Clean Water Act requirements seek to alleviate this problem.

What’s the solution to trash pollution?

Fortunately, cities have several tools to 100% prevent stormwater trash from entering the Bay. Most cities use a combination of all of them. They can install physical barriers known as trash capture devices that filter out trash once it’s entered the storm drain. Trash capture devices can be small screens that are installed on individual storm drains, or large filters that are put downstream of watersheds at the confluence of many storms drains. Or they can act while the trash is still street litter like increasing the amount of street sweeping to keep the trash from building up.

Cities have had to invest heavily to tackle the trash problem, and all of that takes resources, which cities struggle to raise. In fact, most cities that had not yet met their trash elimination requirements cite lack of funding as their number one impediment. Just trash capture devices alone can strain city budgets. Not only do the devices themselves cost money, but they require maintenance and increased staff. The large devices’ maintenance requires a crew to operate heavy machinery and even physically go down into the storm drain system to help manually clean it out. Finding ways to pay for these solutions can delay project implementation – leaving trash to flow into the Bay as a result.

How can cities pay for these solutions?

Cost can be an issue, but there are actions cities can take to make paying for storm drain system upgrades more manageable. A few years ago, the City of San Mateo passed a stormwater fee which is projected to raise $4 million annually and will be used to protect homes and businesses while also addressing pollution. Oakland is in the process of updating its Storm Drain Master Plan as the current infrastructure is aging and vulnerable to threats like sea level rise and trash pollution. Oakland could pass a parcel tax like San Mateo to help meet these needs, and San Jose is also considering passing a stormwater fee. We must also consider the cost of inaction. The storms in January of 2023 cost Santa Clara County $40 million in public infrastructure repairs and over the next 30 years a quarter of homes and half of San Jose’s roads are at risk of flooding. The storm drain system is not an isolated piece of infrastructure. An upgraded system will not only keep trash out of San Francisco Bay waterways like Lake Merritt and our shoreline, but will help with flood prevention, and can be designed to support the creation of more walkable and bikeable streets.

Still, there are other options for financing storm drain upgrades for trash pollution prevention. The recently passed statewide Prop 4 could grant cities money to upgrade stormwater systems to address future flooding needs and pollution risks. Cities can also partner with Caltrans on building infrastructure like large trash capture devices. Caltrans is under similar Clean Water Act requirements and looking to partner with cities on projects. This partnership is beneficial because Caltrans pays for the upfront installation of these devices while cities are only responsible for maintenance and repairs. Many cities have taken advantage of this arrangement, including Oakland, Richmond, and many others that struggle with trash pollution.

What can we do to help?

Of course, the most effective way to stop trash pollution would be to prevent street litter in the first place. As an individual looking at the scale of this problem, it’s hard to feel like you can have an impact, but there are things you can do. First, small actions like reducing the amount of single use plastics you consume are not only good for your health, but the environment. Refill stores are becoming popular and popping up in places all over the Bay Area and are a good way to cut down on the number of plastics you buy for things like household items. While these steps can help us reduce trash, Save The Bay will continue to work with cities to ensure that the trash that does collect on our streets doesn’t end up polluting the Bay.