By Laura Booth – Save The Bay Nursery Fellow

“The history of conservation is the history of how we value nature,” read an illuminating line in Amanda Brown-Stevens’ presentation to attendees at the 14th biennial State of the San Francisco Estuary Conference.

The future of conservation, conversely, will be determined by how we value nature AND people, together.

That was the thesis of this year’s State of the Estuary, where ramping up social-ecological resilience was the key theme, and separating people from nature was acknowledged as an ongoing tactic of oppression.

Connecting People and Nature

More so than in previous years, conference presenters hailed from local community groups, social services branches of local government, and local native communities, in addition to the expected universities, environmental non-profits, and government regulatory agencies.

Brown-Stevens, CEO of Greenbelt Alliance, illustrated just one example of how this change in thinking is altering the actions of environmental stakeholders in her talk about the “long path” of conservation efforts in Coyote Valley, a connective corridor of upland between San Jose and Morgan Hill that, critically, protects groundwater for people who live in the Southern San Jose area—as long as it persists as open space.

She explained that, in the past, conservation efforts in Coyote Valley have waxed and waned in response to external socioeconomic pressures to transform that swathe of land into office parks for the tech industry or housing developments. Now, her organization is asking how they can break this cycle of recurrent battles to keep Coyote Valley protected from inappropriate development forever.

Their chief strategy is to connect to a broader audience than Greenbelt Alliance has ever reached before.

Likewise, the State of the Estuary conference seemed to be reaching beyond its comfort zone to emphasize the voices of people whose principle work—supporting unhoused folks, advocating for affordable housing, conducting faith-based community organizing, and representing historically marginalized groups—is outside the scope of science, design, environmental policymaking, restoration ecology, or regulation.

Human Health is Ecological Health

For the first time, the conference opened with a territorial acknowledgment, powerfully delivered by Kanyon Sayers-Roods, a cross-disciplinary artist and activist representing the Costanoan Ohlone and Chumash peoples. Her closing coyote-yipping echoed in the Scottish Rite’s Grand Auditorium, filling the cavernous space.

Two opening panels reinforced diversity, equity, and inclusivity as the threads weaving later presentations together.

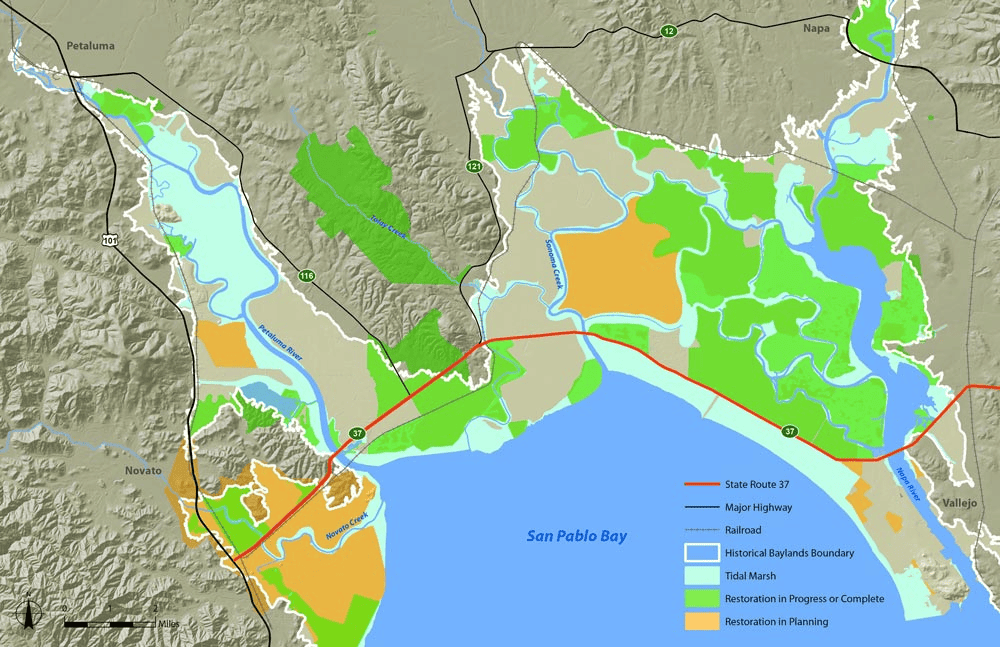

Letitia Grenier opened the “Toward Social-Ecological Resilience: The State of the Estuary Report 2019” by highlighting the addition of emerging, social-ecological indicators of health. Going forward, the report will measure the status and trends in subsided lands, shore resilience, and urban green space—proxies for the ability of human and natural communities to respond to changing climatic conditions. Adding these elements will produce a more accurate measurement of the Estuary’s health that recognizes human health and ecological health are inextricable.

Gabby Trejo, Executive Director of Sacramento Area Congregations Together, said she was reluctant to get her faith-based organization involved in climate change work—until a determined member forced the issue. As they conducted a survey of constituents to capture feelings about climate, she heard from members of her community who were frustrated with the conditions of their housing and air quality; indoor and outdoor air pollution lead to burdens such as asthma and increased infant mortality, particularly in African American communities. “Communities that carry these burdens,” Trejo said, “are not able to relate to the work of scientists,” being occupied with their immediate health. “We need,” she said, “to create a common language, to be able to code-switch ‘data talk’” to connect environmental issues with housing rights, and to pass legislation to keep people from being displaced through the gentrification that, all too often, follows on the heels of greening efforts.

In the “Building Trust: Striving Toward Equitable and Inclusive Outcomes” panel, moderator Nahal Ghoghaie Ipakchie reminded the audience that minority and low-income groups are more likely to demonstrate environmental concern and to identify as environmentalists than higher-income groups and whites. Dealing with stereotypes that dictate otherwise is one of the “difficult conversations” it’s necessary for communities to begin having, said LaDonna Williams, Program Director of All Positives Possible. “If you don’t see color,” she continued, “you don’t see me or listen to me.”

Later in the panel, Beth Rose Middleton Manning, Associate Professor of Native American Studies at UC Davis, picked up the conversation about denial of race and history, noting that “conservation processes are often a-historical.” Among other issues, she highlighted the work of local indigenous land trusts, including Sogorea Te’ Land Trust and Amah Mutsun, to return land in the Bay Area to indigenous stewardship.

These panelists advocated for an ethic of bi-directional learning, where scientists educating community groups on technical information about, for example, the mechanisms of sea-level rise as a consequence of climate change, can also learn from community members about on-the-ground challenges and priorities.

Learning Together

This ethic was actually borne out quite well in the sessions that followed, where the most highly-attended sessions addressed human dimensions of the Estuary.

In “The Next Wave in Conservation: Community-Based and Design Approaches,” attendees in the audience had a chance to ask about the implementation of various community-driven, resilience-oriented projects at a range of scales, from Colma Creek to Houston, Texas, and all the way back to Coyote Valley in the South Bay.

Perhaps the most widely-attended session of the first day was “Humanizing Homelessness for Healthier Creeks and Communities,” where professionals addressing homelessness along the region’s waterways were peppered with questions by audience members wanting their ecologically restorative efforts to result in empowerment and better quality of life for residents, not displacement.

While the mixing of perspectives did occasionally result in drastic switches in tone and lexicon, the discomfort of these moments underscored the newness—and necessity—of the 2019 State of the Estuary’s innovative approach to building resiliency across our dynamic region: through understanding across barriers . After all, as Violet Saena, Resilient Community Program Manager for Acterra, said: “How can we adapt to something we don’t understand?”