A deluge of trash is flowing through Oakland’s storm drains and depositing so much litter in San Francisco Bay that regulators are threatening to levy fines if the city doesn’t do something to tidy up.

A deluge of trash is flowing through Oakland’s storm drains and depositing so much litter in San Francisco Bay that regulators are threatening to levy fines if the city doesn’t do something to tidy up.

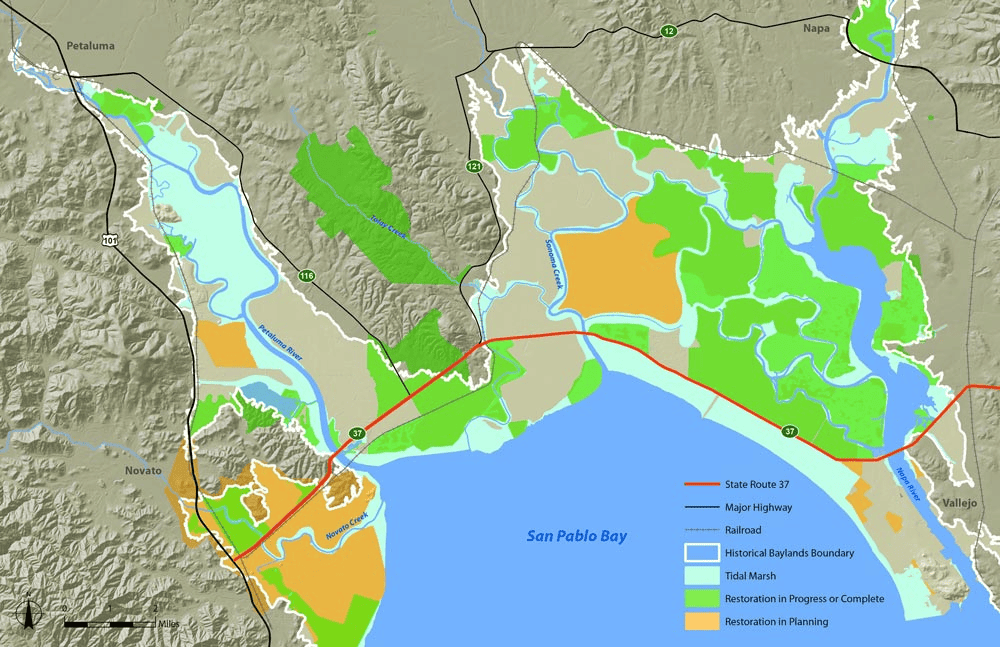

Despite spending millions of dollars over the years on garbage cleanup, Oakland has the Bay Area’s worst record for limiting the rubbish that pollutes creeks, lakes and the bay, according to the San Francisco Bay Regional Water Quality Control Board. The flow of waste violates mandates set by the board to reduce storm drain litter this year by 70 percent compared with 2009, a goal that Oakland is far from meeting. If the city is still in violation on the July 1 deadline, it could face fines of up to $10,000 a day. “They have one of the worst problems per capita,” said Thomas Mumley, the assistant executive officer for the water quality board, which sent a warning letter to Oakland this month. “The problem isn’t Oakland. The problem is all the people who dump the trash in Oakland.” Oakland’s public works committee, made up of four council members, met last week to discuss ways to address the issue. Mayor Libby Schaaf said recently it would cost $20 million to $25 million a year to add trash capture devices to the storm drain system and regulate illegal dumping enough to meet the 70 percent target. “I don’t believe we’re going to meet that requirement by this July,” said councilman Dan Kalb, who chairs the public works committee and is president of Stop Waste, a countywide recycling program. “We agree, they are important goals and we have been making some progress over the years, but it’s just not enough.” Oakland isn’t the only city struggling to comply with the regulations, which apply to the labyrinth of curbside drains, gutters, underground concrete channels, pipes and catch basins that take water off city streets and direct it toward the sea. Last July, 26 of the 70 cities and other municipalities in Alameda, Contra Costa, Santa Clara, San Mateo and Solano counties fell short of the reduction target, which was then 60 percent. Oakland had cut its output 44.6 percent by last year. Collectively, the Bay Area had achieved a 50 percent reduction compared with 2009 — the equivalent of a million gallons of trash. The goals were set eight years ago after the water quality board required local agencies to measure the garbage flowing from storm drains. Regulators were concerned about the 2 million gallons of trash found bobbing in Bay Area waterways, about half of it plastic grocery bags, candy wrappers, lids, straws and chip bags. For each city, compliance is calculated by measuring how much detritus local cleanup programs pull off the streets or out of the drains. More weight is given to the most effective measures, like installing hydrodynamic separators, which capture all garbage flowing down a drain. The amounts cleaned are subtracted from the 2009 baseline. The crackdown is important, conservationists say, because the waste leaches toxins, flows into the bay and winds up in the ocean, where the plastic breaks down into tiny pieces that are ingested by marine mammals, fish and birds. It was an indifferent attitude about litter, experts say, that created the enormous floating garbage patch in the North Pacific, a stew that marine biologists consider an ecosystem catastrophe. In Oakland, where 8,000 storm drain inlets dump into a myriad of creeks, channels and the Oakland Estuary, one of the trashiest waterways is Damon Slough near the Coliseum complex. The muddy banks were strewn last week with aerosol cans, juice bags, hypodermic needles, straws, tennis balls, liquor bottles, candy wrappers and numerous plastic bags. “All of the trash in here is from storm drains at the Coliseum or wind blown from the parking lot,” said David Lewis, executive director of the nonprofit Save the Bay, as he stood next to the foul-smelling slough. “There are five or six creeks that all empty into this area here. It is the pathway, the water column, and it circulates all over.” The stepped-up mandate this year is likely to trip up at least as many cities and agencies as last year, including San Jose, Richmond, Vallejo, San Leandro and Berkeley. San Francisco is exempt from the guidelines because, unlike other cities in the Bay Area, it funnels storm water runoff into its sewer system, which removes the trash before it is discharged. But Oakland’s failure has gotten special attention because it has a larger deficit to make up than any other city, according to a compliance summary prepared by the control board. San Jose is a distant second. “Oakland is the largest source of trash from a city that is not close to compliance,” Lewis said. “It is heavily urbanized, right next to the bay, and the city is not doing what it needs to do to address the problem.” Oakland spends $6.5 million a year on street sweeping and $5.5 million regulating dumping. The city also bans businesses from using foam packaging and plastic shopping bags, but workers still can’t keep up with the litter on the streets, said Lesley Estes, the city’s storm water manager. She said 12 hydrodynamic separators have been placed in storm drains around the city, but that the devices’ price tag of $400,000 to $1 million makes them too expensive to install throughout the system. Oakland’s strategy, she said, is to place mesh pipe screens, which must be cleaned out more often, in all of the drains not covered by the separators. Some 200 screens have been installed during public works projects in high-use areas. Estes, who believes Oakland can reach a 60 percent reduction this year, said she’ll have a clearer picture of the city’s progress when she analyzes data after the fiscal year that closes June 30. She plans to prepare a compliance report and present it to the water quality board by Sept. 30 in the hope that regulators give the city credit for, among other things, its foam and plastic bag bans. No additional money is set aside for storm drain cleanup in the mayor’s proposed budget for 2017-19. “Not all other cities are faced with the same degree of issues that Oakland faces,” Estes said, referring to high priorities like fighting crime and homelessness. “The staff’s commitment to this effort is wholehearted and gung-ho, but it’s a difficult problem, and we just need to figure out the best pathway.” A path Estes would like to avoid is one followed by San Jose, which last June agreed to pay $100 million over the next decade to settle a lawsuit by the nonprofit group Baykeeper for failing to reduce sewage and trash in violation of the federal Clean Water Act. San Jose officials, who said they settled to avoid a lengthy court battle, agreed to clean 32 trash hot spots, including homeless encampments along Coyote Creek and the Guadalupe River, at least once a year. According to regulators, there is a lot less trash emerging from San Jose since the settlement. The storm drain proviso will only get tougher in July 2019, when Bay Area jurisdictions regulated by the water quality board will be obligated to cut garbage output 80 percent. The goal is zero waste by 2022. The board’s Mumley said cities like Oakland could be given more time to meet the coming July 1 deadline, if they outline specific efforts to reduce trash. “My preference would be to give them a chance to solve the problem,” he said, “but ultimately the solution has to be changing public behavior.”

### This article was originally published online in the San Francisco Chronicle on May 30, 2017.