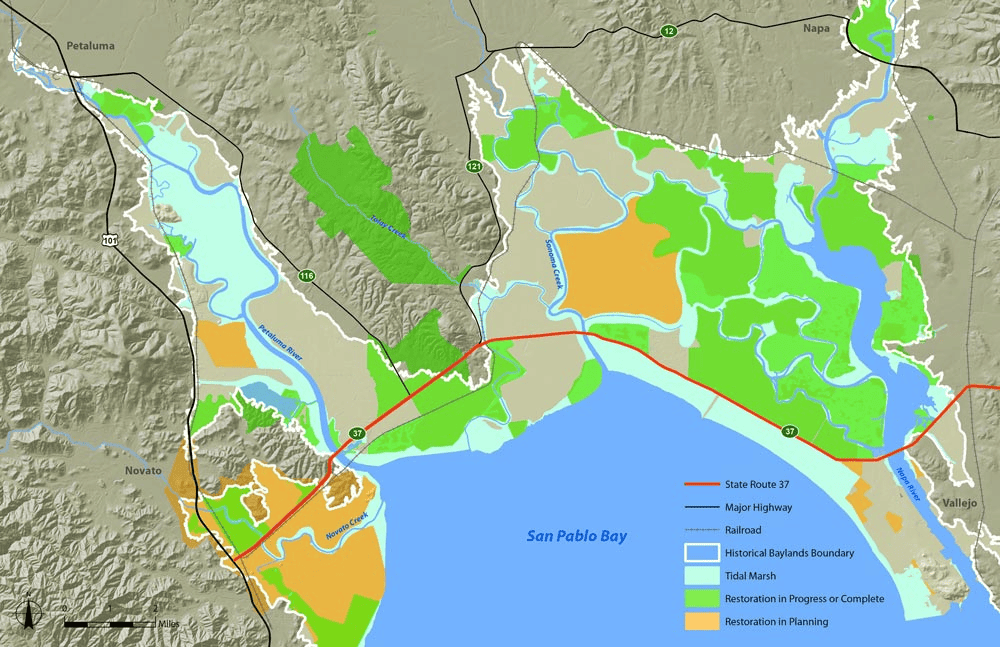

It would be absurd to compare saving the bay to saving the Earth, which will require revolutionary changes in the way all of us on this planet live and work, but it should give us courage and perspective to remember the first environmental activists, who didn’t realize that what they were trying to do was impossible. (How the Bay Was Saved)

Gilliam frequently credited the success of the Save The Bay movement for inspiring other efforts beyond the bay itself, here and around the country: In a time when many Americans feared that their lives and their environment were at the mercy of forces over which they had no control, the save-the-bay success proved that ordinary citizens were not powerless as they confronted the juggernaut of rampant technology and the political clout of giant corporations. It affirmed that they could win against the most formidable opposition. Inspired by that example, residents of other regions organized their own grassroots campaigns to turn back the bulldozers. The traditional American conservation movement, which had been focused on saving wilderness, broadened into the burgeoning environmental movement, concerned with urban as well as rural areas — and ultimately with the Earth itself. He wrote for long enough that he got to describe environmental battles as they happened, like the effort to protect redwood trees in a national park (1966) — and then decades later to inform those enjoying the trees that they were still standing because of a tenacious battle to save them (1982). He wrote about San Franciscans fighting against more freeways plowing through Golden Gate Park and Fisherman’s Wharf (1965) and the Chronicle reprinted that column in 2012 when few residents could imagine that was ever proposed. When San Francisco International Airport proposed filling two square miles of the Bay for reconfigured runways, Harold noted Mark Twain’s observation that history doesn’t exactly repeat itself, but it rhymes. He predicted the public’s love for the Bay would again defeat a developer’s plan to fill it, as San Francisco voters faced a ballot measure giving them the power to approve or deny filling:

San Franciscans have the opportunity to exercise the same kind of people power that broke the tyranny of the bulldozers three decades ago. Other shoreline cities and counties may follow suit, placing ultimate decisions about the entire bay in the hands of the people. And the rhymes of history will be confirmed.

Five years ago, Chronicle urban design writer John King wrote about Gilliam’s lasting impact on San Francisco and the Bay Area:

Without people like Gilliam who fought hard to keep San Francisco and the Bay Area distinct, treasures we take for granted in many cases would be lost. It’s not chance that 1.3 million acres of this region now are protected open space, for instance. It’s because of a shared realization in the 1960s that, to quote a Gilliam column of the time, a concentrated effort of this sort “would preserve for our descendants a share of the superb natural environment enjoyed by our own generation.”

But King also noted Gilliam didn’t dwell on the past – he saw that our region has a psyche that makes us take on challenging causes in part because we have done so before and succeeded. Gilliam called it the “San Francisco psyche … this frame of mind that says innovate, take risks, improvise. You won’t win every battle, but you’ll win the important ones.” Thank you, Harold, for inspiring me and so many others with your words. Read Chronicle columnist Carl Nolte’s obituary for Harold Gilliam here.