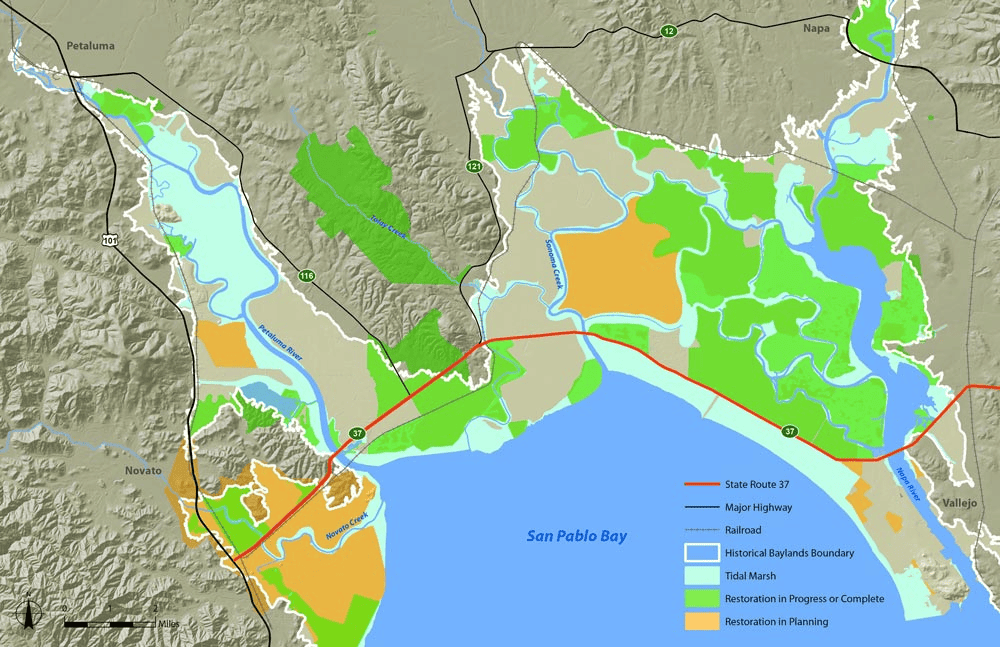

When heavy rains returned to California last winter after an extensive drought, some Bay Area cities experienced flooding for the first time in many years. Now, a new study shows that kind of flooding will become chronic in many Bay Area locations in the decades to come. The Union of Concerned Scientists report provides even more detail on how much climate change will affect specific Bay shoreline cities, and how soon. As early as 2035, neighborhoods all around the Bay Area–on Bay Farm Island, Alameda, Redwood Shores, Sunnyvale, Alviso, Corte Madera, and Larkspur– would experience flooding 26 times per year or more, and that’s with moderate sea level rise. By 2060, the number of affected neighborhoods grows to include Oakland, Milpitas, Palo Alto, East Palo Alto, and others along the corridor between San Francisco and Silicon Valley. If the sea level rises faster, that frequency of flooding will occur sooner. Read the full report at http://bit.ly/2vacc5j. The report raises another problem. The Federal Emergency Management Agency’s maps of flood-prone areas are outdated and don’t reflect sea level rise projections. Those maps determine where property owners can and cannot qualify for federally-subsidized flood insurance, and where communities must construct additional flood protection to retain that insurance. Outdated maps give communities a false sense of security and lead to uninformed development decisions. Just ask those homeowners near Coyote Creek in San Jose who were flooded out a few months ago. The State of California and its agencies, including the Bay Conservation and Development Commission, should be aggressively reducing risks to people and property from climate impacts – that has been explicit in the State’s climate adaptation strategy since 2009. Pressing FEMA for updated maps should be high on the priority list. Here’s a report on the UCS study in the San Jose Mercury News, which quotes Save The Bay:

- By 2060, in the high sea level rise scenario, parts of many Bay Area communities would face flooding 26 times or more per year, or every other week. Communities with affected neighborhoods include Alameda, Oakland, Palo Alto, East Palo Alto, San Mateo, Burlingame, San Francisco, Corte Madera and Larkspur.

- By 2100, in the intermediate sea level rise scenario, chronic flooding would affect public infrastructure such as San Francisco International Airport, Oakland International Airport, San Quentin State Prison, Moffett Federal Airfield and the Bay Bridge.

- By 2100, in the intermediate sea level rise scenario, two Bay Area communities would see more than 10 percent of their land chronically flooded: Alameda and San Mateo.

- By 2100, in the high sea level rise scenario, more than half of Alameda, about 11 percent of South San Francisco and about 14 percent of Oakland’s land area would be chronically flooded.

“Imagine what it would be like to have your driveway and backyard flooded every every other week on average,” Dahl said, “And you can’t let your kids play in the back yard because it’s flooded.” The “low scenario” assumes a San Francisco Bay water level rise of around 2 feet by 2100, a carbon emissions decline, and global warming limited to less than two degrees Celsius — in line with the primary goal of the Paris Agreement. The “intermediate scenario” projects a four-foot water level rise and carbon emissions peaking around mid-century and about four feet of sea level rise globally. In the high scenario, emissions rise through the end of the century and ice melts faster, causing 6.5 feet of sea level rise. The group applauded efforts by cities such as San Francisco and Foster City, which already have begun planning where and how to build seawalls and levees. Other regions — such as the cities of Alameda, Hayward and Oakland and Contra Costa, San Mateo, Alameda and Santa Clara counties — are close behind, identifying potential strategies. Welcoming the report, David Lewis of the Oakland-based nonprofit Save The Bay said it underscored the need for the Federal Emergency Management Agency to update Bay Area flood maps to reflect new projections. Those flood maps determine where property owners can and cannot qualify for federally-subsidized flood insurance, and where communities must construct additional flood protection to retain that insurance. He urged the state to press FEMA to update the maps. Congress also must be prodded to provide funding for the updates, he added. “If maps don’t incorporate projections for sea level rise — and for increased frequency of flooding from extreme storms independent of sea level rise — then communities have a false sense of security, and property values, as well as public and private planning and development decisions, don’t accurately reflect risks,” said Lewis. “Ask those homeowners near Coyote Creek,” which flooded last winter, he said.

This article was originally published in The Mercury News by Lisa Kreiger and Denis Cuff on 7/12/2017.