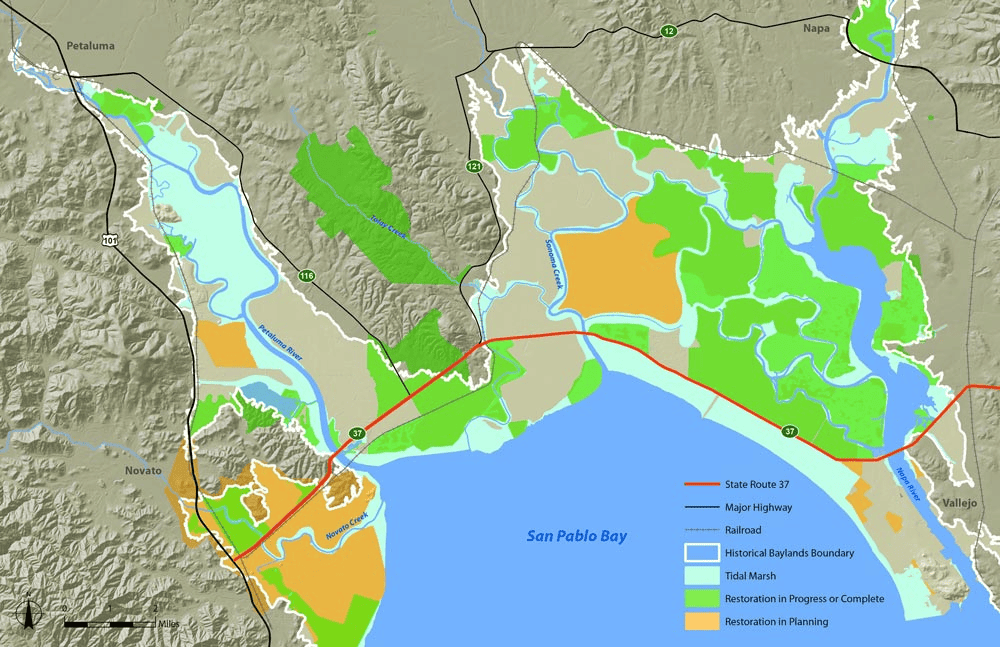

I wonder at first why David Lewis has chosen to meet at Point Isabel, a somewhat nondescript stretch of filled Bay shoreline at the south edge of Richmond. “What we’re standing on shouldn’t be here,” Lewis admits. “But look around!” He gestures toward the hills. “Up there is where Kay Kerr lived.” Kerr, one of the three founders of Save The Bay, the organization Lewis now heads, looked down on this shore when it was a row of active landfills pushing into the Bay—and knew she must take a stand. At home in Kensington, Lewis enjoys a similar but now less alarming view. He gestures toward the Golden Gate. Under a streaky gray December sky is the glimmering reach of the Central Bay, bounded by its three big bridges, cradling its four big islands. In the campaign for Measure AA, the wetland restoration measure, “we learned what people see in their minds when they hear the word ‘Bay’.” It’s this: the bridges, the islands, the cities next to the water. Other stretches of bayshore are wider, wilder than Point Isabel. There are better places, north and south of here, for marshland restoration; there are better places to be alone with a big sky. Lewis is especially fond of China Camp in Marin and the vast expanses near Alviso. “But people like nature with people. That’s what we learned.” Lewis grew up on an urbanized bayshore not unlike this one, in Palo Alto. The waterfront the family liked to visit had everything proper to such a shore: a duck pond, a sewage treatment plant, an airport where they went “to watch planes land,” and a dump. “Of course we went to the dump. The dump was a destination.” His parents “sent in their dollar a year to Save The Bay,” the organization’s original and symbolic membership fee, but Lewis’s activism came home with him from school. During the 1976-77 drought, “I was the water police,” the monitor of running taps and lengthy showers. A summer class in natural history also planted some seeds. These would not sprout, however, for 20 years. After high school, instead of following in his parents’ footsteps to Berkeley, Lewis chose the other coast, winding up at Princeton. He majored in politics and American studies, writing his senior thesis on the evolving nuclear freeze movement in the early 1980s. This interest led him to the arms control field and to Washington, D.C., where he worked successively for Friends of the Earth, Physicians for Social Responsibility, Senator Carl Levin (D-Michigan), and the League of Conservation Voters. But the Bay kept pulling him back. He and his family had already decided on the move when, in 1998, Save The Bay tapped him as its second executive director. It didn’t take long for lobbying skills honed in Washington to come into use in California. In 1998, San Francisco International Airport released a plan to add runways on Bay fill, the first big Bay encroachment proposed since the 1980s. The powers that be lined up in unanimous favor. “It looked unwinnable,” Lewis recalls. Some conservationists toyed with the thought of a grand bargain: SFO would get its expansion but fund the purchase of all the restorable former wetlands around the Bay rim. Lewis wasn’t tempted. “If there was going to be any accommodation, it should be at the end of the environmental review process, not the beginning. Even if we lost, we would have represented the Bay well.” The ensuing campaign followed the classic Save The Bay model—factual, science-based, polite, equipped with reasonable alternatives, implacable—arguing that the airport could clear up its rainy-day delays with gentler, cheaper, more sophisticated means. That would prove to be the case. “Later,” says Lewis, “SFO Director John Martin thanked me.” Lewis would gladly declare victory in the generation-long battle against Bay fill, but “an old-style fight” continues at Redwood City, where Cargill hopes to develop 1,400 acres of crystallizer beds once used for salt production with 12,000 homes. Opposition has slowed down this new juggernaut, and the public is increasingly skeptical of the plan. “Meanwhile, the sea level keeps rising and the traffic gets worse.” The restoration of the wetland rim, more urgent than ever as sea level rise gains speed, is proceeding without Faustian bargains. Lewis threw himself into the campaign to pass Regional Measure AA. Now the citizens of nine Bay counties are taxing themselves to plow ahead with the restoration job. Save The Bay has recently raised and widened its sights, from the here and now to the long-term future and from the immediate shoreline to the wider Bay watershed. The streams that feed the Bay are carrying too much pollution, too many plastic bags, and often too little sediment to help rebuild marshes, Lewis says. “We need to look upland and upstream and influence what’s happening there—the way cities develop and adapt and conserve.” The watershed vision leads to these bold words in the organization’s year-old 2020 Strategic Plan: “We must help save the Bay Area as a sustainable community with a healthy Bay at its heart.” How do you do that? “You build more and deeper relationships where the [land] development is happening, with elected officials and agency staff. You look for community organizations and businesses to ally with. And you go after the money! It doesn’t work otherwise.” Acknowledging that Save The Bay is one of many partners, Lewis notes with pride, “We are more active than others in getting more money. We endorsed ten local ballot measures in November, and nine of them passed.” Walking back to the Bay Trail trailhead, next to the joyful dogs of the Point Isabel off-leash area, we pause at the channel that nourishes remnant Hoffman Marsh. Lewis eyes the waters for bat rays, points out the mud banks where endangered Ridgway’s rails loaf at low tide. Across the marsh is a culvert where an urban creek pours into the tide. This one, it turns out, lacks even a name: It is mapped as Fluvius Innominata. Several neighboring streams, however, have been “daylighted” here and there, reopened to the sky. It’s symbolic of what Lewis is looking for. “Daylighting helps the creeks and builds interest, awareness, stewardship.” He speaks of the tension sometimes felt between access and preservation. “I have no patience with excluding people too much from nature.” He corrects himself: “I have patience with a lot of things, actually. But it’s not necessary to wall off all of the wildlife from all of the people. We have a big enough canvas to have strict nature preserves and recreational access areas, too.”

I wonder at first why David Lewis has chosen to meet at Point Isabel, a somewhat nondescript stretch of filled Bay shoreline at the south edge of Richmond. “What we’re standing on shouldn’t be here,” Lewis admits. “But look around!” He gestures toward the hills. “Up there is where Kay Kerr lived.” Kerr, one of the three founders of Save The Bay, the organization Lewis now heads, looked down on this shore when it was a row of active landfills pushing into the Bay—and knew she must take a stand. At home in Kensington, Lewis enjoys a similar but now less alarming view. He gestures toward the Golden Gate. Under a streaky gray December sky is the glimmering reach of the Central Bay, bounded by its three big bridges, cradling its four big islands. In the campaign for Measure AA, the wetland restoration measure, “we learned what people see in their minds when they hear the word ‘Bay’.” It’s this: the bridges, the islands, the cities next to the water. Other stretches of bayshore are wider, wilder than Point Isabel. There are better places, north and south of here, for marshland restoration; there are better places to be alone with a big sky. Lewis is especially fond of China Camp in Marin and the vast expanses near Alviso. “But people like nature with people. That’s what we learned.” Lewis grew up on an urbanized bayshore not unlike this one, in Palo Alto. The waterfront the family liked to visit had everything proper to such a shore: a duck pond, a sewage treatment plant, an airport where they went “to watch planes land,” and a dump. “Of course we went to the dump. The dump was a destination.” His parents “sent in their dollar a year to Save The Bay,” the organization’s original and symbolic membership fee, but Lewis’s activism came home with him from school. During the 1976-77 drought, “I was the water police,” the monitor of running taps and lengthy showers. A summer class in natural history also planted some seeds. These would not sprout, however, for 20 years. After high school, instead of following in his parents’ footsteps to Berkeley, Lewis chose the other coast, winding up at Princeton. He majored in politics and American studies, writing his senior thesis on the evolving nuclear freeze movement in the early 1980s. This interest led him to the arms control field and to Washington, D.C., where he worked successively for Friends of the Earth, Physicians for Social Responsibility, Senator Carl Levin (D-Michigan), and the League of Conservation Voters. But the Bay kept pulling him back. He and his family had already decided on the move when, in 1998, Save The Bay tapped him as its second executive director. It didn’t take long for lobbying skills honed in Washington to come into use in California. In 1998, San Francisco International Airport released a plan to add runways on Bay fill, the first big Bay encroachment proposed since the 1980s. The powers that be lined up in unanimous favor. “It looked unwinnable,” Lewis recalls. Some conservationists toyed with the thought of a grand bargain: SFO would get its expansion but fund the purchase of all the restorable former wetlands around the Bay rim. Lewis wasn’t tempted. “If there was going to be any accommodation, it should be at the end of the environmental review process, not the beginning. Even if we lost, we would have represented the Bay well.” The ensuing campaign followed the classic Save The Bay model—factual, science-based, polite, equipped with reasonable alternatives, implacable—arguing that the airport could clear up its rainy-day delays with gentler, cheaper, more sophisticated means. That would prove to be the case. “Later,” says Lewis, “SFO Director John Martin thanked me.” Lewis would gladly declare victory in the generation-long battle against Bay fill, but “an old-style fight” continues at Redwood City, where Cargill hopes to develop 1,400 acres of crystallizer beds once used for salt production with 12,000 homes. Opposition has slowed down this new juggernaut, and the public is increasingly skeptical of the plan. “Meanwhile, the sea level keeps rising and the traffic gets worse.” The restoration of the wetland rim, more urgent than ever as sea level rise gains speed, is proceeding without Faustian bargains. Lewis threw himself into the campaign to pass Regional Measure AA. Now the citizens of nine Bay counties are taxing themselves to plow ahead with the restoration job. Save The Bay has recently raised and widened its sights, from the here and now to the long-term future and from the immediate shoreline to the wider Bay watershed. The streams that feed the Bay are carrying too much pollution, too many plastic bags, and often too little sediment to help rebuild marshes, Lewis says. “We need to look upland and upstream and influence what’s happening there—the way cities develop and adapt and conserve.” The watershed vision leads to these bold words in the organization’s year-old 2020 Strategic Plan: “We must help save the Bay Area as a sustainable community with a healthy Bay at its heart.” How do you do that? “You build more and deeper relationships where the [land] development is happening, with elected officials and agency staff. You look for community organizations and businesses to ally with. And you go after the money! It doesn’t work otherwise.” Acknowledging that Save The Bay is one of many partners, Lewis notes with pride, “We are more active than others in getting more money. We endorsed ten local ballot measures in November, and nine of them passed.” Walking back to the Bay Trail trailhead, next to the joyful dogs of the Point Isabel off-leash area, we pause at the channel that nourishes remnant Hoffman Marsh. Lewis eyes the waters for bat rays, points out the mud banks where endangered Ridgway’s rails loaf at low tide. Across the marsh is a culvert where an urban creek pours into the tide. This one, it turns out, lacks even a name: It is mapped as Fluvius Innominata. Several neighboring streams, however, have been “daylighted” here and there, reopened to the sky. It’s symbolic of what Lewis is looking for. “Daylighting helps the creeks and builds interest, awareness, stewardship.” He speaks of the tension sometimes felt between access and preservation. “I have no patience with excluding people too much from nature.” He corrects himself: “I have patience with a lot of things, actually. But it’s not necessary to wall off all of the wildlife from all of the people. We have a big enough canvas to have strict nature preserves and recreational access areas, too.”

This article was originally written by John Hart and posted on Bay Nature Magazine’s website March 28, 2017.